December 05, 2024

The question of how much Tax Increment Financing (TIF) surplus should be used to help close the City of Chicago’s budget gaps is a recurring theme in budget negotiations. In a recent report, the Civic Federation cautioned the City about the use of TIF to fund operational budget gaps. While TIF sweeps, or the use of unallocated funds within a TIF district, may provide temporary budgetary relief, these funds are one-time in nature and not guaranteed to recur every year. Further, the City’s recent bond ordinance calls for a phase-down of TIF use in the City as several districts are set to expire in the next few years, reducing the surplus funding available to fill future budgets.

This short analysis reviews the City of Chicago’s use of TIF surplus between FY2016 and FY2025 to balance operating budgets. A companion report provides an update on TIF districts in Cook County based on data from a report released earlier this year by the County Clerk.

The Civic Federation believes that TIF surplus funds are not panaceas to solve budget shortfalls. The City’s continued reliance on these funds highlights the need for more significant structural reforms (including efficiencies and increased revenues) to put the City in a better financial position.

What are TIFs?

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is a financial mechanism widely used by municipalities and other governments to promote economic development and redevelopment. The use of TIF is intended to generate economic development that would not have occurred “but for” the incentives offered. In Illinois, both counties and municipalities may utilize TIF financing, and TIF districts can receive property, sales, or utility tax revenue.

In property tax TIF districts, the Equalized Assessed Value (EAV) of the district at the time of creation is measured and established as a baseline, which is often called the “frozen” EAV. The EAV of every property in Illinois is the product of the assessed value by the County Assessor (done on a triannual basis based both on land and improvements) and the State Equalization Factor, which is set by the Illinois Department of Revenue. This EAV then determines the portion of property tax levy – or the total money needed to be raised by property taxes - that any given owner will need to pay. In short, the “frozen” EAV of a TIF district is determined by the total property tax levy of a TIF district at the time of its formation.

Within a given TIF district, tax revenues from the incremental growth in EAV over the “frozen” base amount are used to fund redevelopment costs within the district such as land acquisition, site development, public works improvements, and debt service on bonds. Once the redevelopment is completed and has been paid for, the TIF district is dissolved and the increment value – or the difference between the “frozen” EAV and the total EAV - is added to the tax base accessible to all eligible taxing districts. In short, the new value of the property is now able to be taxed by any applicable government entity. Crucially, the increment value is treated as new property when it is added back into the tax base. The return of that value broadens the value of the overall tax base. This does not increase total tax collections, but rather, if the taxing bodies do not raise their levies, it actually leads to a lower annual tax rate for other properties in the TIF district. In Illinois, TIF is authorized for a period of up to 23 years, with the possibility of renewal for an additional 12 years.

It is important to recognize that in counties like Cook County that are subject to the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law (PTELL or “tax caps”), active TIF districts can raise tax rates for their taxpayers higher than they would otherwise have been. The implementation of a TIF district does not freeze or take away tax revenue from overlapping governments such as the Chicago Public Schools and Forest Preserve Districts. This is because tax-capped governments set their levies independent of taxable value, mostly basing annual property tax increases on inflation instead.

TIF districts do not levy taxes and thus do not have tax extensions or tax rates, they only receive tax revenue. The property tax revenues TIF districts receive are the result of applying the tax rates of other taxing agencies to the TIF increment EAV. The same property tax rate is applied to all property in the TIF, both the frozen EAV and the increment EAV. Revenue generated from the frozen EAV amount goes to the taxing districts (schools, parks, etc.) while revenue generated from the increment EAV amount goes to the TIF district.

Chicago’s Use of TIF Surplus to Balance Budgets

According to the terms of the TIF Act, if there is excess money in a TIF district fund annually after funds have been pledged, it is considered to be surplus. Surplus funds must be calculated annually and distributed to overlying taxing districts. The funds must be distributed on a proportional basis; they cannot be directed to a single or select group of overlying taxing districts.

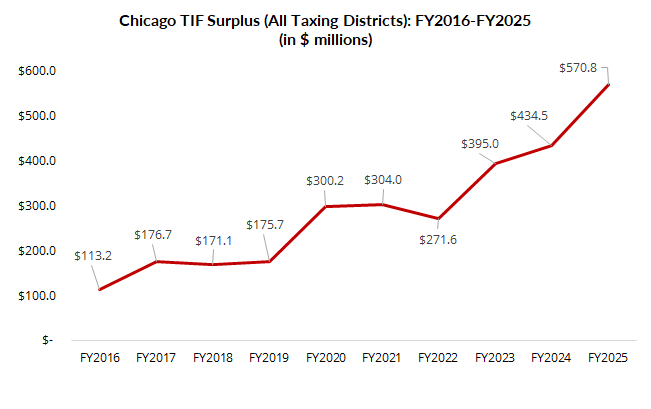

The City of Chicago has continually relied on major sweeps of TIF surplus funds to balance its annual budget, and as the chart below shows, the amount used each year has drastically increased. These sweeps involve identifying funds not needed for current or future redevelopment projects within TIF districts and reallocating it to the City’s general budget. Between the years of FY2016 to FY2025, the City’s use of TIF surplus has increased more than 400% - from $113.2 million to $570.8 million. The FY2025 budget proposes declaring a record $570.8 million in TIF surplus, $131.9 of which will go to the City’s Corporate Fund and $298.1 for Chicago Public Schools.

Such consistently high surpluses could suggest that many TIF districts do not need revenue for redevelopment projects due to unachievable goals and should be terminated. High surpluses also could indicate that a TIF district generates more revenue than needed and some parcels should be released from the district so that their EAV (equalized taxable value) may be returned to the general tax base and relieve some of the burden on other taxpayers.

The continued reliance on these funds for budget shortfalls further perpetuates the Chicago’s broader, ongoing structural imbalance. With the City’s transition away from TIFs for housing and economic development funding via the bond ordinance (see the Civic Federation’s initial reaction), coupled with the large number of districts set to expire in the next few years, it is unlikely that such large surpluses will be available in future years. Further, with other overlapping local governments, such as Chicago Public Schools, also seeking to use of TIF surplus funds to lessen financial woes, there will only be so much of this decreased funding to go around. As budget gaps continue to grow, it is increasingly urgent for the City to find other solutions to replace this safety net in future years.