October 12, 2018

The Illinois Estate tax is levied on net assets over $4 million of the estates of the deceased. Illinois does not have an inheritance tax, which is levied on assets received by the inheritors of an estate.

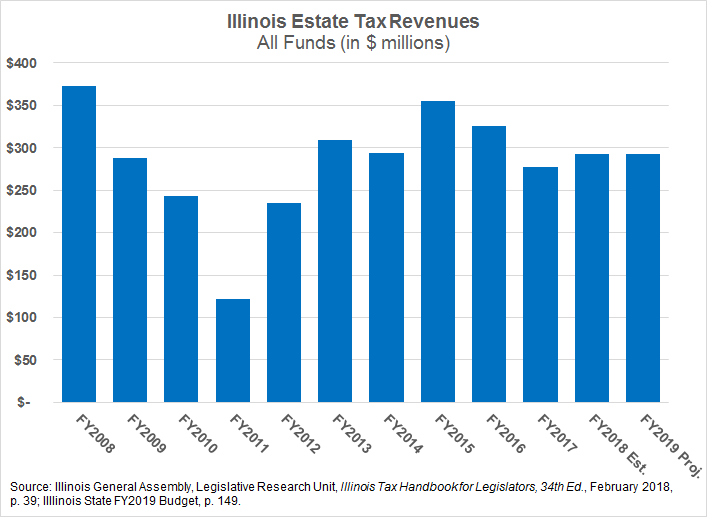

Estate tax revenue is forecast to be $293 million in FY2019, of which 6% will go to the Estate Tax Refund Fund for overpayments. The remaining $275 million will go to General Funds, and represent about 0.7% of total General Funds Revenues. The following chart shows the history of estate tax revenue over the last decade along with projected revenues for FY2019.

While the estate tax has brought in an average of $282 million per year during the last decade, it is one of the State’s more volatile sources of revenue. Part of the volatility stems from the nature of the tax—it depends on the lifespan of a relatively small number of taxpayers. The rest of the volatility has been driven by changes in federal tax policy. The most notable example was the temporary repeal of the federal estate tax during 2010. Although the federal tax was retroactively assessed at the end of the year, the delay resulted in Illinois not assessing any tax on estates of those who died during that year. Accordingly, revenues for FY2011 were abnormally low compared to other years.

Another federal tax change has had an impact as well. Prior to 2001, the federal government offered an estate tax credit for amounts paid for state estate taxes up to certain limits. All states had estate taxes, because they could assess up to the federal credit limits to maximize state revenue without increasing the total tax collected on estates. Many states, including Illinois, directly linked their estate tax statute to the maximum allowable federal credit.

The 2001 federal tax bill began phasing out the federal credit, which was complete by 2005. Now state estate taxes are deducted from the estate before federal estate taxes are applied, similar to the federal income tax deduction for state income taxes. After this change, many states either explicitly repealed their estate taxes or eliminated them by default by remaining coupled with federal tax law.

Illinois and several other states chose to decouple from federal tax policy so that their estate taxes remained in place. It did not change the bracket and rate structure however, which remains identical to those of Maryland, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. The first $40,000 of taxable net worth has a 0% rate, while the top rate of 16% applies to taxable net worth over $10,040,000. Of the 13 states that still have an estate tax, Illinois is tied with nine of them for second-highest top rate. The only state exceeding this is Washington, at 20%. The three states with lower top rates are Hawaii at 15.7%, and Connecticut and Maine, at 12% each.

The only aspect of its estate tax that Illinois has adjusted since the phase-out of the federal credit is the exemption amount. The State raised the exemption from $1 million to $1.5 million in 2004, then to $2 million in 2006, to $3.5 million in 2012 and finally to $4 million in 2013. Because of the bracket structure, the first $4,040,000 of an estate’s net worth pays no tax, while net assets above $14,040,000 are taxed at the maximum rate of 16%.

Over the years the elimination of the federal credit has placed pressure on states to eliminate their estate taxes. In the last year both Delaware and New Jersey eliminated their estate taxes, although New Jersey kept its inheritance tax.

However, more recently federal tax changes have induced states to decouple from the federal government in order to preserve the reach of the estate tax. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 doubled the federal exemption to $11.2 million. Several states that retain the estate tax but were tied to the federal exemption levels opted to set their own, lower exemption levels in order to avoid revenue losses. Illinois, which already set its own exemption level of $4 million, was not affected.

Because most states no longer have an estate tax, there is an incentive for some wealthy people to structure their assets to avoid paying it in Illinois. Strategies include setting up trusts, giving away assets before death, and moving to other states.

Unlike with other taxes, Illinois cannot recoup revenue lost to tax avoidance by simply lowering its rate—the competitive rate is 0%. And although there have been recent calls to eliminate the tax because of its impact on some businesses, it is unlikely that the State can absorb the loss of $200 million to $300 million without other tax or structural changes to replace it.